Impact of Social Media on Children Peer Reviewed Articles

- Enquiry commodity

- Open Access

- Published:

A systematic review of the utilise and effectiveness of social media in child health

BMC Pediatrics volume fourteen, Commodity number:138 (2014) Cite this article

Abstruse

Groundwork

Social media use is highly prevalent among children, youth, and their caregivers, and its use in healthcare is being explored. The objective of this written report was to conduct a systematic review to decide: 1) for what purposes social media is being used in kid wellness and its effectiveness; and two) the attributes of social media tools that may explain how they are or are not effective.

Methods

We searched Medline, CENTRAL, ERIC, PubMed, CINAHL, Bookish Search Complete, Alt Health Scout, Wellness Source, Communication and Mass Media Complete, Web of Knowledge, and Proquest Dissertation and Theses Database from 2000–2013. Nosotros included chief inquiry that evaluated the use of a social media tool, and targeted children, youth, or their families or caregivers. Quality assessment was conducted on all included analytic studies using tools specific to unlike quantitative designs.

Results

We identified 25 studies relevant to child health. The bulk targeted adolescents (64%), evaluated social media for health promotion (52%), and used discussion forums (68%). Most often, social media was included as a component of a complex intervention (64%). Due to heterogeneity in weather, tools, and outcomes, results were not pooled across studies. Attributes of social media perceived to exist constructive included its use equally a distraction in younger children, and its ability to facilitate communication between peers among adolescents. While well-nigh authors presented positive conclusions about the social media tool existence studied (80%), there is little high quality evidence of improved outcomes to support this claim.

Conclusions

This comprehensive review demonstrates that social media is being used for a variety of weather condition and purposes in kid health. The findings provide a foundation from which clinicians and researchers can build in the hereafter by identifying tools that have been developed, describing how they have been used, and isolating components that take been effective.

Groundwork

The popularity of social media has changed the way healthcare providers and consumers access and use information, providing new avenues for interaction and care. This advancement of technology has created an surroundings in which individuals accept the opportunity to participate and collaborate in the sharing of information, and may be particularly relevant for children and youth. In a 2013 written report on adolescents' use of social media and mobile engineering science, researchers from the Pew Internet and American Life Project plant that 95% of teens surveyed used the Internet, a effigy that has remained constant in the United States since 2006 [1]. Additionally, 73% of teens have a cell phone, of which almost half are smartphones [1]. In 2012, Lenhart et al. [2] reported that when teens possess a smartphone, more than 90% use information technology to connect with social networking sites. Even without such a highly connected mobile device, 77% of teens nevertheless logged into social networking sites, and overall, nearly 50% sent daily text messages to their friends [2]. Furthermore, many teens employ multifaceted methods to communicate with their peers, including the Internet, instant messaging, and social networking sites [3].

Considering the all-encompassing caste of connectivity exhibited past today's youth, it may exist worthwhile for healthcare providers to discover ways to engage with teens in forums in which they are already comfortable interacting. Some success has been achieved in the use of mobile engineering (i.e., instant messaging, text letters) for increasing medication adherence and appointment attendance, and it has been noted that many adolescents are using the Net to find health information, specially on sensitive topics (e.g., sexual wellness, drug use) [4]. Given this context, the use of social media tools may be an effective strategy in developing healthcare interventions for children and youth.

In that location is clear interest in how new technologies tin can be used to improve patient outcomes, including in children and youth, therefore we conducted a systematic review to answer two key questions: one) for what purposes are social media being used in the healthcare context for children, youth, and their families, and are they effective for these purposes; and ii) what are the attributes of the social media tools used in this population that may explain how they are or are not effective.

Methods

This systematic review was based on a scoping review that we conducted to determine how social media is being used in healthcare [v]. Child health emerged as an surface area for further study, therefore the scoping review was used equally a foundation, and the search was updated with a focus on children, youth, and their families.

Search strategy

A inquiry librarian searched 11 databases in Jan 2012: Medline, Cardinal, ERIC, PubMed, CINAHL, Bookish Search Complete, Alt Wellness Lookout, Health Source, Communication and Mass Media Complete, Web of Knowledge, and Proquest Dissertation and Theses Database [5]. Dates were restricted to 2000 or later, corresponding to the advent of Web 2.0. No language or study pattern restrictions were practical. The search was updated in May 2013. The search strategy for Medline is provided in the Additional file 1.

Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of studies for eligibility. The full text of studies assessed as 'relevant' or 'unclear' was then independently evaluated by ii reviewers using a standard form. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or adjudication past a tertiary party.

Studies were included if they reported main research, with analytic quantitative designs used to respond whether social media is effective for use in child wellness, and descriptive and qualitative designs used to provide context to attributes that may contribute to the effectiveness or lack of effectiveness of the tools being studied. Further, studies were included if they focused on children, youth, or their families or non-professional caregivers, and examined the use of a social media tool. Social media was divers according to Kaplan and Haenlein'south classification scheme [half-dozen], including: collaborative projects, blogs or microblogs, content communities, social networking sites, and virtual worlds. Nosotros excluded studies that examined mobile health (e.g., tracking or medical reference apps), 1-way transmission of content (e.g., podcasts), and real-fourth dimension exchanges mediated past technology (eastward.g., Skype, conversation rooms) [v]. Studies relevant to pediatric mental health were as well excluded as they are being evaluated separately in a systematic review currently underway. Outcomes were not defined a priori as they were to be incorporated into our description of the field.

Information extraction and quality cess

Data were extracted using standardized forms and entered into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) by i reviewer and verified for accuracy and abyss by some other. Reviewers resolved discrepancies through consensus. Extracted data included study and population characteristics, description of the social media tools used, objective of the tools, outcomes measured and results, and authors' conclusions [vii]. Studies that examined social media as i component of a circuitous intervention were noted as such.

Two reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of included analytic studies and resolved disagreements through discussion. We used the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool to assess randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized controlled trials (NRCTs) [8]. We used a tool for before-after studies that was developed based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [9] and used in a previous review [10]. Quality assessment was not conducted on cross-sectional or qualitative studies every bit they were used to provide additional context to how social media is being used in child wellness, rather than to provide estimates of effect.

Data synthesis and analysis

We described the results of studies qualitatively and in evidence tables. Descriptive statistics were calculated using StataIC 11 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, The states). Studies were grouped according to target user and written report design. When studies provided sufficient data, we calculated standardized hateful differences and 95% CIs for the master outcomes and reported all results in forest plots created using Review Manager, Version 5.ii (The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). We did not pool the results as the primary consequence varied beyond studies; however, we displayed the information graphically to examine the magnitude of effect of the social media interventions.

Results

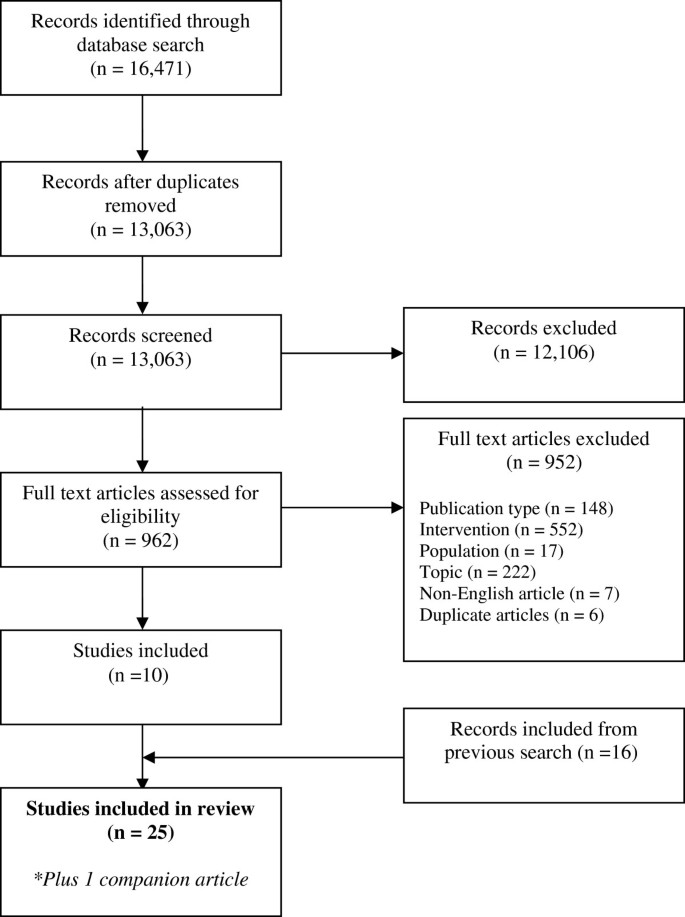

Nosotros identified 25 studies in 26 manufactures that met our inclusion criteria: 16 from the original search [5] and x from the update. Figure 1 outlines the flow of studies through the inclusion process and Table ane provides a description of the included studies. The virtually common uses for social media were for health promotion (52%) and the tools were largely community-based (64%). Adolescents were more than oft the target audience (64%) than children (36%) or caregivers or families (44%; 40% targeted multiple groups). Discussion forums were the most normally used tools (68%). Nearly all authors concluded that the social media tool evaluated showed show of utility (80%) and the remainder were neutral (twenty%); none reported negative conclusions.

Period diagram of written report selection.

How social media is existence used in child health

While social media interventions were used to target health outcomes in children, youth, and caregivers, adolescents were the virtually commonly studied population. 2 studies were based on acute weather; 10 on chronic conditions, with clusters in type one diabetes (n = 3) and cancer (n = 2); and 13 for health promotion purposes, focusing mainly on healthy nutrition and exercise (due north = v), sexual health (n = 4), and smoking cessation (n = two; Tables 2 and 3).

Acute weather

2 studies evaluated social media every bit an intervention in an acute context: i in families of patients in the pediatric intensive care unit [11] (PICU) and one to help parents of children experiencing infantile spasms [12]. While both focused on pediatric health conditions, social media use was directed towards cognition translation efforts, providing a source of information for the caregivers. The authors concluded that the interventions were benign to parents in both cases (Tabular array 3).

Chronic conditions

2 studies conducted in populations with chronic wellness conditions evaluated Zora, a virtual globe [16, 17], and the remaining viii studies investigated the use of word forums (Table 2) [thirteen–15, 18–22]. In each of the ten studies, the primary objective of the social media tool was to provide support to the pediatric patient (north = 3), the parent or family of the patient (north = three), or both (n = 4). These tools were ofttimes in the form of multi-faceted interventions (n = 5), in which the give-and-take forum was just one component. Discussion forums appeared alongside condition-specific data, interactive features, and links to other online and concrete resource such every bit camps and back up groups. Conditions included cancer, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, renal disease, organ transplants, and type 1 diabetes. Adolescents were included in all studies that were intended for the patient; children, ranging from 4 to 12 years old, were also included in five of these studies [xiii, xvi, 17, 19, 22]. Outcomes in this group of studies were near all related to coping or cocky-efficacy, or perceptions and usage of the intervention. 1 study measured the touch on of the social media tool on a modify in a wellness outcome [xv].

Health promotion

Xiii studies evaluated the employ of social media as a wellness promotion tool. Health promotion efforts were directed at children and adolescents, but rarely at caregivers. The two studies that were exclusively aimed at children were focused on salubrious diet and exercise, made employ of discussion forums, and were aimed towards children from 8 to 12 years old [26, 27]. The ii studies evaluating tools intended for caregivers used online educational strategies incorporating word forums [28, 35]. The remaining nine studies evaluated social media use in adolescent populations, covering healthy diet and exercise [23–25], sexual health [29–31], smoking cessation [32, 34], and parenting issues [36].

The largest proportion of health promotion studies was in the area of healthy diet and exercise [23–27]; three of these five studies have been examined in more particular in another systematic review conducted by our grouping [37]. Although near of the social media tools evaluated were discussion forums, in that location was more variety in the health promotion studies in the interventions used than for astute or chronic conditions, including investigations of existing, widely used platforms such every bit Facebook. 4 studies evaluated the use of Facebook equally an outreach strategy to appoint with adolescents in a schoolhouse setting or in the general public [23, 25, 29, 31]. The primary goals of the interventions in the health promotion category were to upshot change in health outcomes, or to act equally educational resources.

Effectiveness of social media in child wellness

We included 12 studies that evaluated the effectiveness of a social media intervention versus a comparator; their results are described below.

Randomized controlled trials

Data were available from seven RCTs. Six trials evaluated discussion forums and all seven trials included the social media tool equally a component of a complex intervention. Only ane report [24] compared 2 social media interventions; two compared the social media intervention to an online tool without the social media component [20, 35], two used a non-technological attribute as the comparing grouping [34, 36], and ii compared social media to no intervention [25, 26]. In all 7 RCTs, there was no significant difference in the primary event measured betwixt the social media group and the comparator. 2 studies [24, 36] used composite measures as principal outcomes and significant benefits were found in private components. The statistical significance of the chief outcomes in these seven RCTs is in contrast to the authors' conclusions, in which four studies concluded that the social media intervention had a positive effect (Table 3).

Quality cess of the RCTs was conducted using the Risk of Bias tool (Table 2) [8]. Two trials were at unclear risk of bias [twenty, 35] and the remaining five were at high hazard of bias [24–26, 34, 36]. Sequence generation and allocation darkening were poorly reported. While the nature of the intervention precluded blinding of participants, blinding of outcome assessors was only reported in two studies [24, 26]. Compunction was loftier, leading to loftier hazard of bias in four studies [25, 26, 34, 36]. Selective outcome reporting was not present in any of the studies.

Non-randomized and before-afterward studies

One NRCT [32] and two before-afterward studies [18, 23] included sufficient information to calculate standardized mean differences. Two studies institute no significant difference between groups [23, 32], and the other establish a significant benefit of social media using ane scale simply not another [18]. Despite these results, two studies [18, 32] claimed that the social media intervention had a positive effect (Table 3).

Using the Risk of Bias tool [8] for the NRCT, and the before-later quality assessment tool, all three studies were poor to moderate quality (Tabular array 2). The before-after studies described the intervention well, but lacked detail on the representativeness of the samples and the reliability of the result measures. The non-randomized controlled trial was at loftier or unclear risk of bias regarding allocation, blinding, and incomplete issue reporting.

Cross-exclusive studies

Two of the included cantankerous-sectional studies evaluated health outcomes following exposure to a social media intervention [27, 29]. One further cross-sectional study [12] found that approximately 60% of YouTube videos on infantile spasms screened depicted accurate portrayals and eighteen.five% of videos were considered to be excellent patient resources.

Attributes of social media associated with effectiveness or lack of effectiveness

While the social media tools and the conditions and outcomes they aim to accost vary widely, we used descriptive, qualitative, and mixed methods studies to explore whether there were overlapping characteristics of social media by and large that may help to explicate their effectiveness or lack thereof.

Cross-sectional studies

Iii cantankerous-sectional studies were used to evaluate users' experiences with social media interventions. Yager et al. [31] investigated the apply of a Facebook site as a source of data on sexual health, and establish that adolescents appreciated the availability of this resource and the comprehensiveness of the information. Braner et al. [xi] and Baum et al. [21] both evaluated tools used to provide support to parents and caregivers and establish that user satisfaction was driven by finding the right residuum between providing informational and emotional support.

Qualitative and mixed methods studies

All vii of the qualitative and mixed methods studies that met our inclusion criteria evaluated social media tools that were intended to provide support to their users. Ii studied a virtual world and v studied discussion forums.

The ii evaluations of Zora, a virtual world designed to help young users explore identity bug, highlighted dissimilar aspects of what fabricated the tool successful. In children and adolescents with end-stage renal failure undergoing dialysis, Zora provided an opportunity for distraction from their affliction, and a ways by which to escape their reality [16]. While healthcare providers felt that information technology would exist an platonic tool to teach their patients about their affliction, none of the children endorsed this view. Conversely, in adolescents who had undergone an organ transplant, communication with others who had been through the aforementioned experience built a sense of community and was a method of coping with their conditions [17].

Mirroring the findings related to the virtual world, the studies evaluating discussion forums found a dichotomy in that some groups preferred to use the social media tools as a distraction from their illness [xiii, 22], while others valued the power to connect with others [14, xv, 19]. One distinction between these ii groups was that younger children tended to be included in those studies that presented social media as a diversion, while adolescents were more highly represented in studies that constitute a benefit in building a social network. In one written report of fathers of a kid with a encephalon tumor, connections with others helped them cope by limiting isolation and normalizing their experiences [xiv]. Even so, other studies found that parents and caregivers were less likely to feel comfortable participating in an online forum [xiii, 15]. Other features identified as being important included maintaining a certain level of activity on the forum in order to attract returning users [19], and minimizing access barriers related to engineering, such as the use of passwords [19, 22].

Discussion

The use of new technology such as social media in kid health is rapidly expanding and evolving. This systematic review provides a comprehensive review of the inquiry that has been conducted in society to serve as a resources to guide future clinical and research efforts in this surface area.

The majority of studies included in our review investigated the employ of a discussion forum and assessed social media as one component of a complex intervention. Word forums were often intended to provide support, and were particularly prevalent in studies of chronic conditions. While in that location were reported benefits in this context, peculiarly from the qualitative investigations, none of the studies that used a discussion forum to outcome change in a health outcome reported significant results. Given the focus on wellness promotion in this group of studies, and the familiarity that children and youth have with current social media platforms, outreach strategies may exist more than effective if efforts are made up-front to identify the tools that the target audience is already using and tailor the intervention appropriately, rather than expect the group to find and adopt new technologies that accept been developed to adjust a more than limited, condition-specific purpose.

The use of complex interventions limits the ability to tease out any effects specific to the social media component; however, the inclusion of qualitative research helped to provide context to some of the attributes that were perceived to be effective. In general, users were nigh drawn to the ability of social media to facilitate the evolution of a back up network. This did not apply to all populations, though, and tended to be more relevant to older children, and parents or caregivers. In the study populations including younger children, the reported reward of the social media intervention tended to prevarication within its ability to serve as a distraction from their disease.

The utilise of social media varied according to the blazon of condition studied. Tools applied to acute conditions targeted the parents, and were intended to be educational resource and promoted data sharing. As described to a higher place, provision of support, either to the patient or to the caregiver, was the primary goal in chronic conditions. Health promotion was the category that most directly targeted children and youth, and demonstrated the greatest variety in tools used and outcomes measured, mayhap indicating potential for future development.

The authors' conclusions tended to be positive with respect to the effectiveness and promise of social media as an intervention or promotional tool for child health. Yet, this was rarely supported past the statistical significance of the results. While this is a new technology with enough of advocates and hypothesized benefits, at that place is no articulate evidence that it is effective in improving health outcomes in children and youth. The included studies were of poor to moderate quality and many did not use rigorous study designs. Moving forward, an emphasis on well-conducted experimental designs and qualitative research, rather than on descriptive studies, would help to illuminate whether social media demonstrates effectiveness, and what characteristics contribute to that potential impact. This could include an increased focus on head-to-head comparisons of the effectiveness of specific social media tools, qualitative evaluations of their perceived strengths and limitations, and the use of changes in health outcomes as end-points.

Strengths and limitations

We conducted a comprehensive systematic review of the literature following well-endorsed methods [38, 39]. Our results provide a view of how social media is being used in child wellness, including the target audiences and intended purposes. Nosotros included all study designs including qualitative and descriptive research in order to provide information to help understand how these interventions may or may not be constructive. These results may aid inform the development of hereafter interventions and research. The limitations of this review pertain to the nature of the topic and the methodological quality of the main inquiry. Specifically, in the majority of studies, social media was used as ane component of a complex intervention making it difficult to tease out the specific impact of the social media modalities. Further, the primary inquiry in this area had methodological limitations that should be addressed in time to come enquiry. For example, in randomized and non-randomized trials, attention should be focused on adequate sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinding of outcome assessment. Attrition was problematic and may be reflective of the claiming of maintaining engagement with the target audience through the interventions employed. Integrating end-user engagement in the development of the social media tools or strategy may be a step in overcoming this obstacle in future research [40]. Finally, while this review provides a thorough examination of the bookish literature, the nature and development of social media has left a gap between tools that are currently used and those that have been scientifically evaluated. Other tools may have been developed that were not captured in our search of formal bookish investigations. Therefore, the findings of this review may point towards an absenteeism of evidence, rather than bear witness of the absence of effectiveness of social media as a strategy for health-related interventions in children and youth.

Conclusions

This systematic review demonstrates that social media is beingness used extensively in child health for a variety of purposes. The most common uses for social media were for wellness promotion with a focus on healthy diet and do, sexual wellness, smoking cessation, and parenting bug. Adolescents were the almost common target audience, word forums were the most normally used tools, and the tools were largely community-based. Nearly all studies concluded that the social media tool evaluated showed evidence of utility; however, results of the master outcomes from the majority of comparative studies showed no meaning consequence. This synthesis offers an important resource for those who are developing and evaluating interventions involving social media.

Abbreviations

- NRCT:

-

Non-randomized controlled trial

- PICU:

-

Pediatric intensive care unit

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial.

References

-

Madden M, Lenhart A, Duggan M, Cortesi S, Gasser U: Teens and Technology. 2013, [http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Teens-and-Tech.aspx]

-

Lenhart A: Teens, Smartphones & Texting. [http://world wide web.pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Teens-and-smartphones/Summary-of-findings.aspx]

-

Lenhart A, Madden K, Smith A, Macgill A: Teens and Social Media, Report: Teens, Social Networking, Blogs, Videos, Mobile. [http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2007/Teens-and-Social-Media.aspx]

-

Schurgin O'Keeffe G, Clarke-Pearson K, Council on Communications and Media: The touch of social media on children, adolescents, and family. Pediatrics. 2011, 127 (iv): 4-

-

Hamm MP, Chisholm A, Shulhan J, Milne A, Scott SD, Given LM, Hartling 50: Social media use among patients and caregivers: a scoping review. BMJ Open up. 2013, 3 (five):

-

Kaplan AM, Haenlein M: Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus Horiz. 2010, 53: 10-

-

Tricco AC, Tetzlaff J, Pham B, Brehaut J, Moher D: Non-Cochrane vs. Cochrane reviews were twice equally likely to have positive conclusion statements: cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009, 62: 8-

-

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (Table viii.4a). Edited by: Higgins JPT, Dark-green South. 2011, Cochrane Collaboration, [http://www.cochrane-handbook.org]

-

Wells Thousand, Shea B, O'Connell J, Robertson J, Peterson V, Welch 5, Losos K, Tugwell P: The Newcastle-Ottawa Calibration (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-assay. [http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.Asp]

-

Bond Chiliad, Ospina M, Blitz S, Friesen C, Innes G, Yoon P, Curry Chiliad, Holroyd B, Rowe B: Interventions to reduce overcrowding in emergency departments. 2006, Ottawa: Engineering science Report 67.4

-

Braner DA, Lai South, Hodo R, Ibsen LA, Bratton SL, Hollemon D, Goldstein B: Interactive Spider web sites for families and physicians of pediatric intensive care unit of measurement patients: a preliminary report. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004, 5 (5): 434-439. x.1097/01.PCC.0000137358.72147.6C.

-

Lim Fat MJ, Doja A, Barrowman N, Sell E: YouTube videos as a teaching tool and patient resource for infantile spasms. J Kid Neurol. 2011, 26 (7): 804-809. 10.1177/0883073811402345.

-

Ewing LJ, Long K, Rotondi A, Howe C, Bill L, Marsland AL: Brief report: A pilot written report of a spider web-based resource for families of children with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009, 34 (v): 523-529. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn096.

-

Nicholas DB, Chahauver A, Brownstone D, Hetherington R, McNeill T, Bouffet Due east: Evaluation of an online peer support network for fathers of a child with a brain tumor. Soc Work Health Care. 2012, 51 (3): 232-245. 10.1080/00981389.2011.631696.

-

Stinson J, McGrath P, Hodnett E, Feldman B, Duffy C, Huber A, Tucker 50, Hetherington R, Tse Due south, Spiegel L, Campillo S, Gill N, White M: Usability testing of an online self-direction program for adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Med Internet Res. 2010, 12 (3): e30-10.2196/jmir.1349.

-

Bers MU, Gonzalez-Heydrich J, Raches D, DeMaso DR: Zora: a airplane pilot virtual customs in the pediatric dialysis unit of measurement. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2001, 84 (Pt:1): 1-4.

-

Bers MU: New media for new organs: A virtual community for pediatric mail service-transplant patients. Convergence. 2009, 15 (4): 462-469. 10.1177/1354856509342344.

-

Merkel RM, Wright T: Parental self-efficacy and online support among parents of children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Nurs. 2012, 38 (6): 303-308.

-

Nordfeldt S, Hanberger 50, Berterö C: Patient and parent views on a Web two.0 Diabetes Portal–the management tool, the generator, and the gatekeeper: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2010, 12: 9-10.2196/jmir.1347.

-

Whittemore R, Gray M, Lindemann E, Ambrosino J, Jaser S: Evolution of an Cyberspace coping skills training program for teenagers with type i diabetes. Comput Inform Nurs. 2010, 28 (ii): 103-111. 10.1097/NCN.0b013e3181cd8199.

-

Baum LS: Internet parent support groups for main caregivers of a kid with special health care needs. Pediatr Nurs. 2004, 30 (5): 381-401.

-

Nicholas DB, Darch J, McNeill T, Brister 50, O'Leary K, Berlin D, Koller DF: Perceptions of online back up for hospitalized children and adolescents. Soc Work Health Care. 2007, 44 (three): 205-223. 10.1300/J010v44n03_06.

-

Cordeira KL: Furnishings of a Wellness Advocacy Program to Promote Physical Activity and Diet Behaviors Among Adolescents: An Evaluation of the Immature Leaders for Salubrious Modify plan MPH Thesis. 2012, School of Public Health: The University of Texas,

-

DeBar LL, Dickerson J, Clarke G, Stevens VJ, Ritenbaugh C, Aickin G: Using a website to build customs and enhance outcomes in a group, multi-component intervention promoting healthy diet and practise in adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009, 34 (v): 539-550. ten.1093/jpepsy/jsn126.

-

Lao 50: Evaluation of a social networking based SNAP-Ed nutrition curriculum on behavior change MS Thesis. 2011, Department of Nutrition and Nutrient Sciences: University of Rhode Island

-

Rydell SA, French SA, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Gerlach AF, Story K, Christopherson KK: Utilise of a Web-based component of a nutrition and physical activeness behavioral intervention with Girl Scouts. J Am Nutrition Assoc. 2005, 105 (9): 1447-1450. x.1016/j.jada.2005.06.027.

-

Savige GS: E-learning: a nutritionally ripe environs. Food & Nutrition Message. 2005, 26 (2:Suppl 2): S230-S234.

-

Cox MF, Scharer K, Clark AJ: Development of a Spider web-based program to improve communication about sex. Comput Inform Nurs. 2009, 27 (1): 18-25. 10.1097/NCN.0b013e31818dd3c5.

-

Jones K, Baldwin KA, Lewis PR: The potential influence of a social media intervention on risky sexual behavior and Chlamydia incidence. J Community Health Nurs. 2012, 29 (two): 106-120. x.1080/07370016.2012.670579.

-

Lou CH, Zhao Q, Gao ES, Shah IH: Can the Internet exist used finer to provide sex teaching to young people in Cathay?. J Adolesc Health. 2006, 39 (5): 720-728. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.003.

-

Yager AM, O'Keefe C: Adolescent Apply of Social Networking to Gain Sexual Health Information. J Nurse Pract. 2012, viii (4): 294-298. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2012.01.016.

-

Chen HH, Yeh ML, Chao YH: Comparison effects of auricular acupressure with and without an cyberspace-assisted program on smoking abeyance and cocky-efficacy of adolescents. J Altern Complement Med. 2006, 12 (2): 147-152. 10.1089/acm.2006.12.147.

-

Chen HH, Yeh ML: Developing and evaluating a smoking abeyance program combined with an Net-assisted instruction program for adolescents with smoking. Patient Educ Couns. 2006, 61: 411-418. ten.1016/j.pec.2005.05.007.

-

Patten CA, Croghan IT, Meis TM, Decker PA, Pingree S, Colligan RC, Dornelas EA, Offord KP, Boberg EW, Baumberger RK, Hurt RD, Gustafson DH: Randomized clinical trial of an Internet-based versus brief office intervention for adolescent smoking cessation. Patient Educ Couns. 2006, 64 (1–3): 249-258.

-

Baggett KM, Davis B, Feil EG, Sheeber LL, Landry SH, Carta JJ, Leve C: Technologies for expanding the achieve of evidence-based interventions: preliminary results for promoting social-emotional development in early on babyhood. Top in Early Child Spec Educ. 2010, 29 (4): 226-238. 10.1177/0271121409354782.

-

Hudson DB, Campbell-Grossman C, Hertzog G: Effects of an internet intervention on Mothers' psychological, parenting, and health care utilization outcomes. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2012, 35 (3/4): 176-193.

-

Williams G, Hamm MP, Shulhan J, Vandermeer B, Hartling Fifty: Social media interventions for healthy nutrition and do: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2014, 4 (2): e003926-x.1136/bmjopen-2013-003926.

-

Chandler J, Churchill R, Higgins J, Lasserson T, Tovey D: Methodological Standards for the Bear of New Cochrane Intervention Reviews. Version ii.2. [http://www.editorial-unit of measurement.cochrane.org/sites/editorial-unit.cochrane.org/files/uploads/MECIR_conduct_standards%202.two%2017122012_0.pdf]

-

Establish of Medicine: Finding what works in health care: Standards for Systematic Review. 2011, Washington, DC: The National Academies Printing

-

Hartling Fifty, Scott S, Pandya R, Johnson D, Bishop T, Klassen TP: Storytelling equally a communication tool for health consumers: development of an intervention for parents of children with croup. Stories to communicate wellness data. BMC Pediatr. 2010, 10: 64-10.1186/1471-2431-10-64.

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this paper can exist accessed here:http://world wide web.biomedcentral.com/1471-2431/14/138/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Annabritt Chisholm, Michelle Foisy, and Baljot Chahal for assistance with study pick, and Ben Vandermeer for his assistance with the statistical analysis. This review was supported by a Knowledge-to-Action Grant from Alberta Innovates – Wellness Solutions. The sponsor had no office in the design and conduct of the study; drove, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; grooming, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Dr. Scott holds a Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Translation in Kid Wellness and Population Health Investigator Award from Alberta Innovates – Health Solutions. Dr. Hartling holds a New Investigator Salary Accolade from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Author data

Affiliations

Respective writer

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they take no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MPH, SDS, and LH designed the study. MPH coordinated the project and is the guarantor. AM conducted the literature search and contributed to drafting the manuscript. MPH, JS, GW, and AM screened manufactures and performed data extraction and quality assessment. MPH and LH interpreted the data. MPH drafted and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary textile

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This article is published nether license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/i.0/) applies to the information made bachelor in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Virtually this article

Cite this article

Hamm, M.P., Shulhan, J., Williams, G. et al. A systematic review of the utilise and effectiveness of social media in child health. BMC Pediatr 14, 138 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-xiv-138

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-138

Keywords

- Social media

- Pediatrics

- Systematic review

Source: https://bmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2431-14-138

0 Response to "Impact of Social Media on Children Peer Reviewed Articles"

Post a Comment